Ferret News

What we know about how ferrets sleep

By Tim Marsh

Animals need sleep

Sleep is critical for the health and well-being of many animals. We feel irritable when we don’t get enough sleep, and our thoughts seem foggy. This is not only a common experience for mammals like us, but nearly all animals need some form of sleep to function. Even insects have been proven to need sleep, and their memory suffers when they don’t get enough sleep. For example, fruit flies can be trained to prefer flying down a dark tunnel when it has food and the light tunnel has a repellant. But sleep-deprived fruit flies take longer to train and more quickly forget which tunnel is best.

Being sleep deprived over longer periods of time makes the immune system malfunction, causes or increases many other health problems, and, in extreme circumstances, results in death. According to Guidelines for the Care and Use of Mammals in Neuroscience and Behavioral Research, “Sleep deprivation of over seven days with the disk-over-water system results in the development of ulcerative skin lesions, hyperphagia, loss of body mass, hypothermia, and eventually septicemia and death in rats.” Animal studies have shown that within a couple of weeks, insufficient sleep causes a reduction in the number of circulating leukocytes (commonly known as white blood cells). White blood cells are the body’s defense system, fighting against infectious diseases and other invaders. Because of this, animals that are getting enough good sleep are more likely to survive infections and diseases.

Setting the right conditions for ferret sleep

We care a lot about the conditions in which we sleep. If we’re too cold, if the bed or pillow is too hard, if it is too bright or noisy, we will do something about it or at least complain. But ferrets can’t tell us when something is bothering them. We are intuitively aware of the best conditions for our own sleep. But we are not always accurate when guessing the needs of other animals.

In our article on ferrets’ preferred temperature for sleep (“It’s Getting Hot in Here,” issue no. 10, March/April 2018), we talked about the Thermal Neutral Zone (TNZ), which is the temperature range in which the ferret does not have to put any effort into maintaining its preferred body temperature. When a ferret is inactive, such as while sleeping, she produces less heat and needs a warmer environment to remain comfortable. But there is no set figure for this because different ferrets live in different environments. Animals can adjust to their climate by growing more fur or thinning their blood. So a ferret conditioned to a cold country will prefer different conditions compared to a ferret conditioned to a hot country. The only way to know what suits your ferret the most is to give her some options and see what she does.

Options work well for allowing a ferret to choose the right temperature. Plenty of bedding options is a must. However, some things, like light and noise levels, we have to choose for them. In many ways, ferrets are like playful children and by keeping the lights on, some will want to play longer than is good for them. We also have to consider how good their senses are when trying to consider how dark or quiet they need it to sleep well.

Sleep is an evolved behavior

When trying to imagine what a ferret needs, often the best we can do is imagine what we need and hope that this also meets their needs. But there is a good reason why our needs and ferrets’ needs are different.

Not all mammals evolved at the same time. A long way back down the trunk of our evolutionary tree, we find the monotremes. These are egg-laying mammals, including the platypus and the echidna, and they evolved about fifty million years ago. The Mustelidae branch of mammals, which gave us the ferret, evolved about twenty to thirty million years ago; scientists are still narrowing the date range. This means that our little friends have some very ancient qualities. These include their kidney shape and some of their skull features.

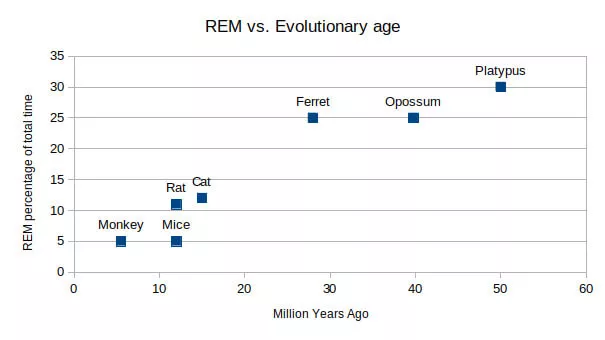

Through the use of equipment that can accurately measure the tiny signals in a ferret’s brain without interfering with its lifestyle or sleeping behavior, science has discovered other ancient remnants of mammalian evolution. It appears that the nature of sleep has evolved. Modern mammals like humans, cats, and rats have two different states of sleep with brain activity patterns as distinct from each other as they are from our awake mind. These are known as Rapid Eye Movement (REM) sleep and non-REM sleep. But in the monotremes, the echidna and the platypus, these states do not show the same distinction and there has been some disagreement about whether they can be detected at all. Instead, their sleep appears more like that of prenatal mammals.

There appears to be a correlation between the amount of REM sleep required and how recently evolved the mammal is. Ferrets require more REM sleep than cats and monkeys. Their REM requirements are more similar to the platypus and the opossum, which share other primitive traits. When looking at the amount of REM sleep required by a mammal versus how long ago it appeared on the evolutionary tree, there is a clear clustering into two groups. Mammals that evolved more than 20 million years ago require at least 25% of their time to be REM sleep. More recently evolved mammals require only about 10% REM sleep. We speculate that this change indicates a sudden evolutionary change in sleep.

Another aspect of sleep which appears to have evolved is the ability to sleep for only one long period per day. Unlike us, ferrets sleep for many short periods a day. Research indicates that a ferret is typically awake about eight times a day for extended periods but wakes many more times than that for short moments. They spend about 30% more time awake during light periods of the day than they do while it is dark. But just because they spend a lot of time awake when it is dark does not mean that they don’t care if it is light or dark. When they do sleep, the type of sleep they have is affected by light and dark, and they need both. Ninety minutes is around the longest they remained awake at any one time during that study.

There is currently a lot of disagreement regarding how much a ferret sleeps. This is partly because, like humans, there is a lot of variety between ferrets. But to some extent, it is also caused by the difference between how laboratories and owners detect sleep. Ferrets can spend a lot of time in a drowsy state which, according to brain wave analysis, is not technically sleep. But to an observer seeing the ferret breathing slowly with closed eyes and not moving, it looks a lot like sleep. Ferrets also sleep more when it is cold, when there is less daylight than darkness, when they are very young, and when they get quite old. According to brain wave analysis in lab-based experiments, ferrets slept for about 14.5 hours each day.

Taken together, the data tell us that ferret sleep is very different from human sleep. We can’t guess their needs by considering our own or expect them to just fit in with our lifestyles. To give our ferrets the best opportunity to get their full quota of sleep and remain healthy, we need to manage their needs on their terms.

Ferrets respond to seasonal changes

The Earth orbits the sun while spinning on a tilted axis. That tilted axis creates the seasons of our year. For half of the year, days are longer than nights (summer), and for the other half nights are longer than days for most places on Earth (winter). Ferrets evolved to make the most of these seasonal changes by shedding fur as summer approaches and growing it again for the winter. There are other seasonal changes like putting on weight, but one of the most important is the annual breeding cycle.

A ferret’s body knows the season by the hours of daylight. This light information comes into the ferret’s body through its eyes, via the retina, to a series of organs designed to manage the ferret’s internal cycles. How bright that light is and what color it is can make a difference to some systems, but the most important factor is the duration of daylight. And changes to this duration can have a measurable impact in as little as two weeks.

Current and Future Options for Non-Surgical Neutering of Ferrets states, “Female ferrets (jills) are induced ovulators and therefore remain in estrus until they are mated, or for as long as daylight lasts longer than 12 hours [per day].” Currently, vets and scientists believe that early sterilization and excessive exposure to light may be causative factors in adrenal disease, especially for ferrets in the United States. Adrenal disease is one of the most common ferret illnesses, and there is reason to believe unnatural and excessive light exposure is playing a role in it. This is supported by the fact that the ferret’s physiology creates a direct link between the periods of light exposure and the production of melatonin, which is part of a signaling pathway to the adrenal gland. This results in the adrenal gland being continuously overstimulated when the ferret is exposed to extra light. And there is a link between overstimulation and unwanted cell growth, which is the basis for adrenal disease. Once adrenal disease has begun, there is no evidence that a natural light cycle can correct it. But there is speculation that a natural light cycle may reduce the likelihood of developing adrenal disease in the first place. To our knowledge, thus far there are no scientific studies that have tested this hypothesis.

The easiest way to provide a natural light cycle if you live outside of the tropics is to keep your ferret where she is exposed to natural light and remove or block any artificial light. Just take care that any windows are not letting in artificial street lighting or some other source. Street lighting might not seem like much, but a study of the tammar wallaby in the wild showed that its reproductive cycles were affected by artificial lighting. If natural lighting is not possible, then there are timers which can be used to control lighting. These may need adjusting as the seasons change.

Ferret dead sleep

If you’ve never experienced this, it is best to know beforehand. There may come a time when you go to feed or play with your darling ferret, and at first they seem asleep. A warm, floppy, deep sleep. Then after picking her up, prodding her, rubbing her belly and more, she does not respond at all. Your heart pounds because at some deep level, you know that was enough to wake any person up. But ferrets aren’t people, and they have the ability to terrify their owners by going into ferret dead sleep.

There is nothing wrong with this, and it indicates nothing more than they were tired and you did a great job of providing them a place where they felt very safe to sleep. To be sure they are okay, you might want to check that their gums are still pink, listen carefully for a heartbeat if you can’t feel it, and try to see if they are breathing. Sometimes the breathing is hard to detect, but if their heart is still beating steadily, their breathing must be fine. Once you’re sure they are still healthy, just let them sleep and leave them to wake up on their own terms.

A restful environment

In addition to seasonal light cycles and preferred temperature, there are a few other things that can ensure your ferret gets a healthy amount of sleep. Let’s start with noise. Brains are very good at getting used to patterns. Many people who live near regular sources of noise like flight paths or train tracks find that they don’t notice them after a while. Ferrets will do the same, so long as the noise is regular or predictable, it will have no impact on them.

The sounds made by a television or sound system are not predictable. They can include just about any noise, in any order, and are often designed to grab attention and hold interest. So when choosing what needs to be quiet to let your darling sleep, ignore it if the refrigerator buzzes, or a fan clicks regularly, but keep the unpredictable and unusual sounds to a minimum, and remember their great sense of hearing.

A safe bed is a good bed. Ferrets like to burrow, so getting into and under things to sleep comes naturally to them. Provide them with options, and even when they have chosen a favorite, leave them some other choices because ferrets like to change things up every now and then. Dark spaces like a box or pipe can provide a feeling of security. Hammocks are often a favourite, and versatile blankets can be crawled under and arranged to suit.

Make sure their cage area is large enough that they can sleep away from their litter tray or toilet area and not end up rolling in their food or wet by their water. Plenty of play time and enough space to exercise in can wear them out and also help them sleep well.

References & further reading

Jha, Sushil K., Tammi Coleman, and Marcos G. Frank. “Sleep and Sleep Regulation in the Ferret (Mustela putorius furo).” Behavioural Brain Research, volume 172, issue 1. Published in 2006. Accessed 20 February 2019. Pages 106-113. (Scholarly article)

National Research Council of the National Academies. Guidelines for the Care and Use of Mammals in Neuroscience and Behavioral Research. Published by The National Academies Press in 2003. (Report)

Shoemaker, N.J., Johannes Thomas Lumeij, and A. Rijnberk. Current and Future Options for Non-Surgical Neutering of Ferrets (Mustela putorius furo). Book chapter submitted for publication. https://dspace.library.uu.nl/bitstream/handle/1874/305/c10.pdf. Accessed 20 February 2019. (Online book chapter)